The vast territory gave us our first images of the bush and has become a respite for families from hot cities

Thirteen kids are sitting around the campfire. It is a little after supper and the youngsters are waiting for darkness to descend before setting out on the night’s adventure. They will play a game called manhunt – a supersized version of hide and go seek – in a huge area of thick bush at Brent campground in Ontario’s Algonquin Park.

This is the north side of the park, where there is less pressure from the hordes who swarm into this vast wilderness each summer to seek a taste of the wild life, see a moose or two, catch a fish and roast marshmallows around the campfire.

I am with two other dads and we have brought six children with us. They are among the excited kids around the fire on a lakeside campsite, which we purloined by telling a family already installed that we had a reservation.

(The father of that family took two hours to dismantle his tents and shelters – in good-natured fashion – and move them to a campsite nearby.

Unknown to us at the time was the fact the campsite was available on a first-come, first-served basis, and he got there first.)

We had reached the Brent campground by driving six hours from Montreal – most of it along Highways 417 and 17 in Ontario and then another hour on a dirt road after turning off at Deux Rivières. The extra driving is the price for a quieter corner of this beautiful park, which has provided the

quintessential Canadian experience of camping and canoeing in the northern woods for more than 100 years.

Stark scenes of the park – trees bent by the wind, rock and white-capped lakes – have been burned into the consciousness of Canadians thanks to copies of paintings of the Group of Seven and their associates hanging in schools everywhere. At the southeastern corner of the park, Tom Thomson’s cabin sits on the shore of Grand Lake at Achray, once a whistle-stop of the Canadian National Railway. In 1916 he sketched Jack Pine with nearby Carcajou Bay in the background.

Few wilderness areas have received such high-profile attention over the years (the park is even a part of mystery literature thanks to detective Benny Cooperman), and few are so close to major urban centres and can provide a welcome respite from the hot asphalt, pulsing cursors and workplace piranhas.

It’s a great place for families as the campfire scene will attest, and kids quickly break down barriers to organize their own events, a process that evokes an earlier era when youngsters roamed more freely in their neighbourhoods.

I have taken my two children into the park on half a dozen occasions, and the hardest part is dragging them back to the car to go home. There is something simple, yet undefinable, about the joy of searching for frogs in the weeds close to shore, roasting hot dogs on the campfire or playing manhunt.

Visitor from England

The rules are always simple: Don’t drown, don’t fall in the fire and don’t get lost. In other words, don’t do anything that would upset your mother.

And if you do, then mum’s the word.

In an early trip to the park, my friend Bob Johnston (he’s the guy who persuaded the father at Brent to tear down his camp and move to a nearby site) and I took a visitor from England to the park’s Lake Opeongo for his first (and only) trip into the Canadian wilderness.

While the lake is large, you can feel part of a greater community in the evening as fires flicker at campsites across the water. It’s a soothing feeling to know that you are not alone in the cosmos, whose vastness is defined by the twinkling stars above. The same sight might have evoked similar sentiments in our cave-dwelling ancestors.

On our third and last night on the lake, the three of us camped at a site on the east side that was large, open and breezy. Around the campfire we discussed the possibility of sighting a bear, a not-unheard-of experience in the park.

“If a bear comes to the site, he’ll get you guys first,” Johnston said, pointing to the tent occupied by the visitor and myself.

That night, I slept like a dead man, as did Johnston. Poor Pete, the visitor, his imagination running wild, tossed and turned for hours.

His nervousness was not so far-fetched. Two years later, a couple from Toronto were killed by a rogue bear on a nearby island during a Thanksgiving weekend trip.

http://algonquinpark.on.ca/virtual/canoe_routes_map/index.php

Precautions are essential when communing with nature. Hang your food well off the ground at night so as not to attract animals and keep a safe distance from the moose, which are plentiful. You can see them grazing at the side of Highway 60,

which cuts across the southern portion of the park, or in swampy areas in the interior.

We’ve seen them while paddling from Proulx Lake to Big Crow Lake on a five-day trip that we have done twice, 10 years apart.

And there’s more than wildlife. On the second occasion, we camped at Big Crow for two nights and took a 11/2-kilometre hike to see giant white pine, a virgin stand, that was somehow missed by the logging companies that moved through this area in the 19th century.

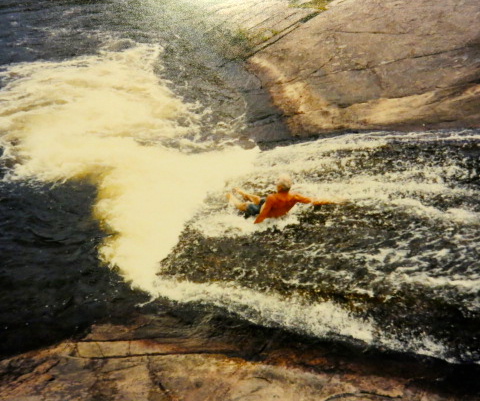

The next day we paddled and humped our canoes and packs down the Crow River. We must have done six or more portages because of the low water.

Close to exhaustion as we struggled into Crow Bay, we were then hammered by a severe rain storm for half an hour or more.

We were soaked and cold as we dragged our canoes up an embankment at a campsite, set up a tarp and changed into dry duds.

The first course for supper consisted of oatmeal cookies and two beers each, which I had hauled over those portages in my backpack. The second course consisted of grilled cheese sandwiches, and they have never tasted better.

You win popularity points with your fellow trippers for surprising them with a few beers, but the park authorities frown on bringing cans into the interior. (A friend was fined a few years ago for having a bottle of wine, which a ranger spotted at a portage.)

The next day we paddled through Lake Lavieille, Hardy Bay and Dickson Lake without seeing a soul.

There’s a good reason for that. The most direct route between Dickson Lake and the East Arm of Opeongo includes a 5.3-kilometre portage – one of the longest in the park and a back-straining hump that takes two to three hours.

On the first occasion doing that portage in the early ’90s, one of our bedraggled trippers – his name was Moe – begged us not to leave him behind.

He caught up to us as we made camp in the disappearing light at the end of the portage.

Slow Moe never came camping with us again.

We now call him No Mo’ Moe.

But that’s Algonquin Park for you. It can split you apart or bring you together like the kids around the campfire anticipating an adrenalin-charged game of manhunt.

Good to Go

Algonquin isn’t just for canoeists. Bring your bikes if you’re planning on a stay at a campground.

For families there is the Old Railway Bike Trail, a 10-kilometre run (very easy) through the bush from Mew Lake to Rock Lake.

If you want a bigger challenge, try the Minnesing Mountain Bike Trail, which is 23 kilometres and took me and my son close to four hours, although experts can complete it in three hours. There are three shorter loops of 4.7, 10.1 and 17.1 kilometres.

If backpacking appeals to you, trails run off Highway 60 – the Western Uplands Backpacking Trail and the Highland Backpacking Trail.

Reservations are essential for campsites. You can do it all starting at http://www.ontarioparks.com/ online.

There are well-equipped stores at Canoe Lake (www.portagestore.com), Oxtongue Lake (just outside the western entrance), Lake Opeongo and Brent

(algonquinoutfitters.com) on Cedar Lake. You can rent canoes at the stores. The stores will also arrange canoe trips and other services such as a water taxi.

You can also book cabins.

Campers speak out about their favorite fishing holes and other glories of the park at http://www.algonquinadventures.com/ online, and Mark Rubino has set up his own page, http://www.markinthepark.com, to describe his trips over the past five years.

Leave a comment